TIBET

Hubert von Goisern: Tibet Travel Diary 1996

Lhasa, 7th May 1996. Tseten and I have been here at the airport for about two hours now, together with about 50 tourists, who have flown in from Europe and America. Passport and visa control is advancing only slowly. Two uniformed Chinese men are working, six more are standing around observing. A young woman, also a soldier, is particularly busy and every five minutes she meticulously straightens the line of people waiting. Pieces of luggage need to be in a straight line too.

Thick as thieves in thin air

The altitude of 3800 metres causing trouble for most people. Some lean exhausted against the wall. An older woman, a Canadian, fans herself with her passport. The Chinese woman gets rough and pulls her back into line. A group of Tibetans, who arrived on the same plane, are being checked in a separate room - away from public view. Nothing would happen without bribes, they told me beforehand. You simply relinquish something of what you've brought with you.

Passport control. I don't have any problems. Tseten is thoroughly scrutinised. She has a European passport. But her appearance is Tibetan, as is her name. But there's nothing conspicuous about her on the computer. And soon we're standing outside and are in Tibet. For me it's a dream come true.

For Tseten too. She was three years old when she fled into exile with her parents and her entire family. That was in 1961 and since then she has dreamed of coming back sometime, but postponed the journey time and again, because she was afraid. The fear is justified. Her mother went back to Tibet for a visit in 1987 and was promptly arrested. She sat in jail for six years.

I met Tseten by chance six months ago and when she told me the story of her life and the stories of suffering of her people, I persuaded her to make this journey with me. With the argument: "Come with me and we'll see for ourselves. It can't be as bad as you say."

I knew the situation from her descriptions, from books and knew that Tibet had been occupied by China for almost 50 years. A country where human rights abuses have taken place nonstop since the Chinese have been there. But all these stories of torture and atrocities and spying seemed exaggerated to me. I should be undeceived.

A bus takes us from the airport to the city centre. The oxygen deprivation alternately makes me feel euphoric - or depressive, when something appears that doesn't fit with the beautiful picture: for example the huge area of concrete buildings on the bus ride into the city. "Development and Research Centre" is written in English on a sign. Inside of course sit soldiers - a special unit, which responds when there are problems in Lhasa, Tibetans later tell us.

We take up lodgings in a hotel near Barkhor, the district in which the Tibetans are still allowed to live the way they want to. The Tibetan ghetto constitutes about 5 per cent of the area of Lhasa. The other 95 per cent of the Tibetan buildings were knocked down by the Chinese and Communist functional buildings were constructed in their place - with the aesthetic quality of shoeboxes.

Although we're tired and fighting our shortness of breath, we don't stay in the hotel. We set off on foot to explore the city and immerse ourselves in the colourful hustle and bustle of the market. We are soon taken up in the stream of pilgrims that is moving clockwise through the alleys around the Jokhang temple.

Time and again we, or rather Tseten, are spoken to by Tibetans, who see her as one of them, but one who has come from the west. We are pulled into dark corners and made aware that you cannot speak freely with each other on the street here.

Then I see them too, the surveillance cameras. If you're as careless as to hold a conversation for a while in an open street or alley, it's not long before, as if just by chance, a policeman is standing next to you listening it. Anyone who thinks that the Tibetans, who were always looking to talk, complained about the situation or bemoaned their fate, is wrong. They are curious. They want to know if we've heard anything of the Dalai Lama and if he's coming back soon. They have faith in a speedy end to Chinese occupation: "It can't go on like this!"

Waiting for the Dalai Lama's return: the Potala

The poverty of the Tibetans in Lhasa cannot be missed. Farmers have to beg, because they cannot survive the winter on their summer earnings. Behind restaurants people wait for scraps. We meet a father and son. The boy is about six years old and has a severe eye infection. When Tseten asks the man why he hasn't taken the boy to a doctor or to the hospital, he just says that he can't afford it. Is there no social institution that looks after the ill? Yes, there's a doctor that would do it. But he's overrun with people who are really ill.

A young guy who speaks broken English offers me his services as a guide. I turn him down, but we get to talking and I ask him if he learned English at school. He laughs and says that he couldn't ever go to school in Tibet. He learned his English in a Tibetan school in Dharamsala, the North Indian city in which the exiled Tibetan government is based. Most of his friends have never gone to school.

He returned to Tibet two years ago with about 40 school friends, because their families had been asked to make them do so by the Chinese. If they had not returned, their parents would have lost their jobs in the administration. They were promised that all the children would receive a suitable apprenticeship in Tibet. In fact, not one child received the promised school place. Instead, the 16 - 18 year olds ended up in a prison for three to twelve weeks, where they were insulted, humiliated and reeducated.

Tibetan children, said the young man, hardly have access to schools. As a policeman approaches, he conspicuously takes a turquoise from his trouser pocket and offers it to me for sale with a laugh. But before I can answer, he leaves. The policeman strolls past and returns to his observation post.

I'm tired, I feel exhausted. Tseten feels slain too. We go back to the hotel. I sit in the lobby there and watch the tourists for a while. I get the feeling that only very few of those going in and out here are getting any notion of the real situation. For the majority of them it's an adventure, an exotic stamp in their passports.

I envy their naïve impartiality. There are some magazines on a table, among them an English-language Communist pamphlet. I flicked through it and found a quotation from Lenin. "A nation that rejects arms deserves to be treated like slaves." If those are their principles, it is no wonder that the Chinese have no respect for the peaceful Tibetans.

No, I'm not a Buddhist, but I like these people here on the Roof of the World. I like the way of the Tibetans. I like the way they laugh - in spite of everything. And there's another difference from the Chinese. They don't laugh. They only smile. At most. They have lost even that in Tibet.

On this four week journey through Tibet I've seen hundreds, thousands of laughing Tibetans and a total of three laughing Chinese people. Two of them were very drunk.

The next morning we visit the Potala and in the afternoon Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama's summer residence. Former. Tseten and I talk less and less about what we're seeing and hearing. We withdraw and try, each for themselves, to process everything. But it doesn't work.

My Tibetan companion has a nervous breakdown the next day. We stay in the hotel room the whole day, drinking tea and trying to talk about what is going on inside us.

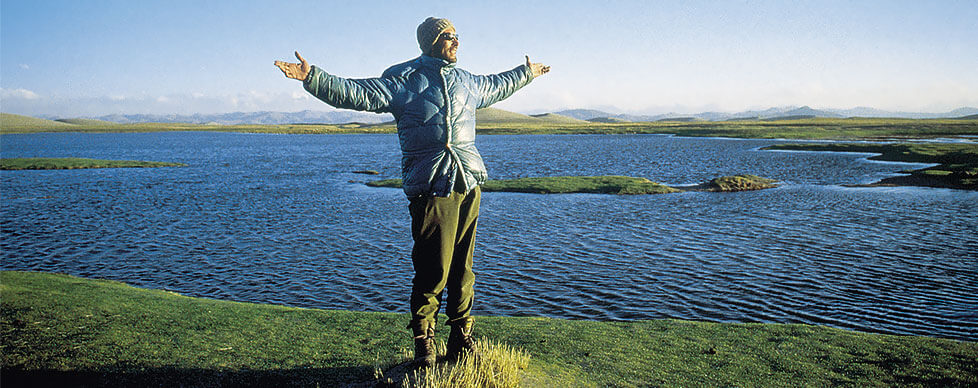

For the following days we hire a jeep with a driver and guide to go up north. To Nam Tso, the second biggest lake in Tibet.

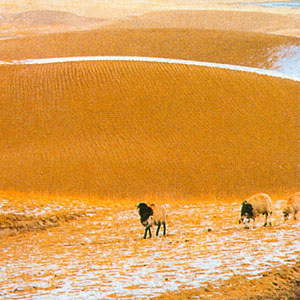

Yaks in fresh snow on sand dunes

It's 10th May 1996. Somewhere out in the country. I am completely overcome by the landscape. Snow and glaciers coat the mountains all around. In between are endlessly wide valleys, thousands of half-wild yaks are scattered like black dots across the unending plains and hills along with sheep and shaggy goats.

Hither and thither are nomads' tents. Sometimes you see them sitting at a little fire near the road. With a can in which they boil water for their tea. Time plays no role here any more. Everything is nature. Great, vast nature.

A feeling of ecstasy comes over me. But then images of Lhasa push in between and this wonderful feeling breaks apart. I become depressed, I am completely at the mercy of my emotions. They come in waves. Like the landscape through which we are travelling.

We reach a pass. At 5200 metres we get out, tie prayer flags to a mast and call: "Lakije Lho" - the Gods will triumph. Hopefully, I think to myself.

Before us lies the enormous Nam Tso, surrounded by 7000m high snow-topped mountains. On its shores are nomads and herds of yaks. We spend the next two nights in a tent at the shore of the lake.

Although the sun is directly above us it is bitterly cold and I'm pleased I have my down jacket with me. A strong, unrelenting wind shakes our clothes and our tent too, late into the night. At some point the wind dies down and instead it begins to snow.

When I climb out of the tent the next morning, the mountains all around are white and there is a thick layer of hoarfrost on our tent. For breakfast there is the traditional nomadic food for the first time: tsampa, roasted barley flour mixed with butter and salty butter tea.

Tsampa always tasted good to me, even on the last day, when I said a melancholy goodbye to this very healthy dish. It was different with the Tibetan tea. It tasted very good at the start and I couldn't get enough of it. But after two week I'd drunk too much of it and longed for a warm sugary drink. For me the Tibetan tea was more of a soup.

After breakfast we take a walk. Not far from the tent there is a cloister, bedded into the caves of the cliffs, where a couple of nuns live. We visit the temple. I buy a slingshot braided by the nuns and practise firing stones into the lake. Tseten talks to a nun and discovers that she entered the cloister when she underwent an enforced sterilisation at 18.

We then climb the mountain behind the cloister. It's very tiring as we are not yet well acclimatised. But when we stand at the summit, the lake at our feet, with our tiny tent on the shore and the deep blue sky with its bright white, constantly changing cloudscapes above us, we find peace. The silence that surrounds us enters our hearts too. And for half an hour we forget all grief and are simply happy.

Highly symbolic gift from the Chinese to the Tibetans: "Golden calves"

The next day we return to Lhasa. We have to spend two more days there in order to obtain the necessary permits for our journey to the west. On the road to Lhasa we meet a convoy of military transport vehicles. Lorries with soldiers and material. Once the endless number of army vehicles have passed me, I decide to start counting the vehicles. I count almost two hundred. Added to those that had already passed, I estimate that about 300 military vehicles are on their way towards Lhasa. Our guide has become visibly nervous and says that something must have happened. When we reach Lhasa there are additional roadblocks and checks all over, in the city we discover the reason for the commotion too.

There was a shooting in Ganden, one of Tibet's three biggest cloisters, not far from Lhasa. A military patrol marched into the cloister and requested that the monks come out with all the pictures of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, something they were not prepared to do. When the monks refused to produce these pictures, things got rough and ended in a shoot-out, in which four monks were seriously injured. One died.

One must add in advance that pictures of the man whom Tibetans still recognise as their spiritual and political leader were forbidden for a long time. Until at some point the regulations were relaxed and his photographs were permitted to be sold and to stand on altars.

Interestingly these pictures were only available from Chinese traders. Only they were supplied. So the Chinese made a good business from it. Perhaps it was because the market was saturated, or perhaps it was down to an arbitrary whim of a general or mayor that it was decided that these pictures should all be collected up again.

A day later a great crowd of people gathers in one of the streets. We find out that the Chinese military are driving a lorry through the streets with the 20 monks in chains. On the one hand to humiliate them, on the other to make clear what will happen to those who do not subordinate.

I feel the urge to go and take pictures. But Tseten panics and asks me to stay. She wouldn't cope with seeing such a thing. I want to go alone, but she doesn't allow that either, because she's worried that I could be arrested.

I'm not worried about myself. I reckon that the worst they could do is put me on an aeroplane tomorrow and expel me from the country. In deference to Tseten, I stay with her.

17th May 1996: Gyantse. I'm ill, very ill. Tseten is ill too. We must have eaten something bad. I woke in the night with vomiting and diarrhoea. My heart is racing, I'm dizzy. I'm listless. We arrived here yesterday from Lhasa. It rained the whole day. We arrived very late in this wonderful city. Just as the clouds lifted and the sun came through.

Into the Fifties Gyantse was a centre for woollen goods and weaving work. Nearly all the city's inhabitants made their living from it. Until the border to Nepal was closed.

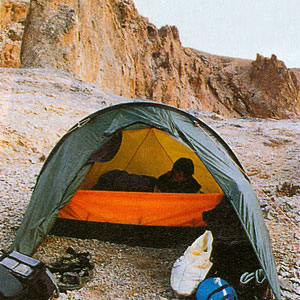

Tseten in our tent

In the evening after our arrival we head off to visit the famous cloister. The sun sits low on the horizon and bathes the monastic compound in a warm soft light. Only four of the original sixteen buildings have survived the cultural revolution.

Right in the reception area there is a nasty great stone inscription, on which is written that it was the Chinese who declared this cultural monument to be worth protecting and preserving and so they saved it for the world.

I think to myself that they really have no sense of embarrassment. It is actually the case that the monks are the ones who are doing the restoration work. They receive no support from the government and in many cases are even prevented from restoring the buildings to their former glory. It is nonetheless a place that allows you to feel and savour the deep intellectual and spiritual concentration that for centuries was practised here.

However contemplation is soon disturbed by an atrocious noise that suddenly descends upon the city. It is the sound of Chinese marching music, not dissimilar to our marching music as is known all over at home. In addition a female voice blares out slogans in Chinese. I discover that this radio play is executed every evening. When I look around I see a column with loudspeakers on a hill in the middle of the city. The whole thing lasts about two hours and is of such volume and impertinence that we can still hear it in our room after we've returned to the guesthouse.

The next day in the morning the day begins again with brass music and the shrill female voice, which announces to all that a wonderful morning has dawned and it would be a happy life, that we lived in a very happy time in a beautiful world and that the work awaits us, to make this beautiful world yet more beautiful.

It won't be the last time that we meet this propaganda machine, this noise disturbance, this acoustic rubbish, on our journey through Tibet. George Orwell imposes himself.

Despite my ill health we continue forth at midday. I am only vaguely aware of the landscape that passes me. I direct all my instincts towards coming to a destination somewhere. When we reach Shigatse late in the afternoon I'm already feeling somewhat better. I haven't seen much of Shigatse, because there's not much to see in Shigatse.

The city is a spawn of ugliness. Apart from a cloister, and even this is only a facade, not one single Tibetan building remains. It is a city that could be anywhere and nowhere. I stay in the hotel room and turn on the television.

I can't believe my eyes. The Austrian Federal Chancellor Franz Vranitzky is on the Chinese news. Evidently they were agreed about something, as only smiling faces were to be seen. Unfortunately I can't understand the announcer.

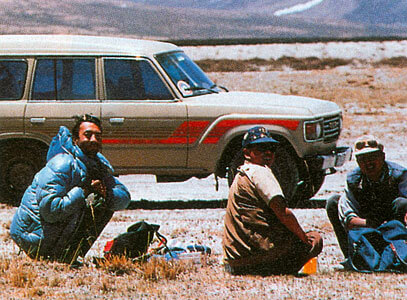

Short break for the driver, the guide and the much tested car

The next day we continue to the Rongbuk cloister at the foot of Mount Everest, or Chomolongma, as the Tibetans call it. The cloister is at 5000 metres above sea level in a landscape that couldn't be any more impressive for someone who, like me, likes mountains.

We spend the night in a room that the monks put at our disposal, make soup and let the silence and grandeur of the mountains work their effect on us. The next day I get up at five o'clock and walk on a small hill behind the cloister. At home we'd call it a mountain. I sit on a rock and watch nature awake.

A monk, wrapped in blankets, beats a gong and slowly monks and nuns emerge from the houses and quarters of the cloister. They are hooded to protect themselves from the cold and stream towards the temple.

With its rays the sun colours the icy snowfield golden and the bluish haze in the deep valleys slowly yields to the light. In a place like this, I think to myself, it is perhaps difficult to live, but easy to pray. And I regret having to leave again soon and feel the desire to return here again one day.

22nd May. The car has broken down - again. The first damage was a broken head gasket. Then there was some gearbox defect. Now it's something with the universal coupling. The driver repairs everything himself. We're somewhere in a Chinese satellite settlement, where we have got hold of an important replacement part.

I couldn't get to sleep for a long time again last night. In order to dam the flood of thoughts I thought of green. At first just the colour green, then the jungle, warmth, rain, tropical rain, tropical sun. I thought of Africa and of the Kailash.

We travelled the whole day. The wind is shaking my nerves. There is no escape. The landscape, with huge gentle hills, behind which on one side the Himalaya and on the other side the Trans Himalaya loom, offers no protection at all. We set up camp in an old abandoned sheep pen.

There's no roof. But we are somewhat more protected here. But again and again the tent is by tent is seized by a gust of wind and shit flies through the air, crumbly sheep shit.

A few hours later: the shit was too much for us. We packed everything up into the car again and drove on.

Prayer flags on Döhma La. The pilgrims' path around the Kallash leads 5700m above sea level

To a dirty guesthouse between Manasarova Lake and Mount Kailash. I'm tired. But it's not just the altitude that is afflicting me. It's the whole journey, in particular the dirt, the poverty, the remoteness, the distance from home, from the children and from friends. How very much I am used to my world. Since leaving home there hasn't been any what that you could drink without boiling it first. There's only ever tea or soup when you're thirsty. I'm longing for my water, my spring, my house. I couldn't live in this vegetationless world permanently.

The landscape is impressive, the people are charming and friendly, but I feel lonely and no longer full of the joys of life.

23rd May, at the foot of the Kailash: The preparations for the hike around the mountain, which will take three days, are finished. Tseten and I walk around the camp, a colourful Tibetan tent city with merchants and monks, children and elderly people.

I enjoyed the day. I am reconciled with the land again. And with myself. The people, who have all come here out of religious motivation, emanate strength and faith. Many, most of them, have made sacrifices to come here. An elderly Indian man died from the exertion yesterday. And two pilgrims from Singapore had to be carried down from the pass. I have respect for the undertaking and pray that all will go well.

In any case I'm looking forward to the movement, to walking, the days in the natural world without the car. Eight hours of walking are behind us. In front of our tent is the north face of the holiest mountain in the world. Tseten is worried that it could turn very cold in the night. I reassure her that we will withstand it well.

A bit of exposure can't hurt. We've certainly had a lot of it, but I think that hiking around the Kailash will be the high point of our journey. And thus the high point of effort and hardship too. But the high point of connection with heaven and earth as well.

The north face of the Kailash stands before us in all its majesty and harmoniousness. Now and again the wind takes a spray of snow from the summit and carries it into the evening sky. The weather is beautiful, but windy with strong, almost angry gusts. During our advance we had a snowstorm and rain too. We have set up the tent in the shelter of an old derelict cloister. A pilgrim family have set up camp beside us. We drink tea together. I feel happy.

The next evening. The passage has been made. It was an enormous effort. I often felt faint. Especially in the last two 200 metres ascent. Making the feeling of standing at the top all the more wonderful. We spent probably an hour there. I couldn't get enough of seeing the many pilgrims. Some must only have been eight or ten years old. Others were as old as the hills. You could see from the traditional clothes they were wearing that they came from all over. From Kham, from Arndo, from Kyrong, from Phurang, from Lhasa. There were mothers who carried two-year-olds on their backs. Most of them were only wearing light cotton plimsolls and some of them who measured the 50 kilometre route in body-lengths.

Somewhere in the west of Tibet

And they all laughed and called out prayers to be answered to the sky and the mountain, that it give the Dalai Lama a long life and free Tibet. We spent an hour there and then headed down. First of all with the wonderful feeling of having managed the most difficult part, a beautiful landscape before our eyes and then ever more in a trance, putting one foot in front of the other, jumping over rocks, crossing streams, until we arrived dead tired at the Milarepa cloister at six o'clock in the evening.

25th May. We are back in Darchen, the starting point of our round trip. A few lorries and jeeps are standing around. The midday sun isn't enough to warm me. Although there is barely any wind blowing I'm sitting here with my down jacket and hood. Now and again someone limps across the courtyard. Victims of the circumnavigation of the Kailash.

The next day, 8 o'clock in the morning at Manasarovar Lake. We have set up our tent not far from a hot spring. And I want to take a bath this morning. The water is steaming, it smells sulphurous. It smells the same as in the spa hotel at home in Goisern.

A shaggy black donkey leans lazily on a wall and enjoys the morning sunshine. The peak of the Kailash juts out behind a long drawn out brown hill and from the stovepipes of the mud huts behind us billows smoke from dried dung, the standard Tibetan fuel. My fingers are numb until I dip them into the hot water.

Somewhere in the west on the return journey. I crawl out of the sleeping bag and open the tent. Before me lies a fantastic landscape of a grass steppe, little dark blues lakes and enormous sand dunes, behind which the snow-topped mountains of the Himalaya soar.

2nd June, in the border town of Zhangmu. For breakfast there is tsampa one last time. I have a mixed feeling in my chest. On the one hand I feel relief and joy at having the efforts and deprivations behind me. On the other hand I'm sad to leave this country behind me. Not least because it's very uncertain, whether I will ever return.